Prehistoric Australians might not have had to worry about losing their keys or being audited by the taxman, but one thing that might have troubled an Aussie hominid mind during the Pleistocene? The possibility of getting scratched to death by a huge cat with a pouch on its tummy.

Thylacoleo carnifex (Greek for "pouched lion executioner") was probably the largest carnivorous marsupial ever to have lived, showing up in the fossil record around 2.5 million years ago and disappearing only in the last few tens of thousands of years. Their existence overlapped with that of early humans — they feature in some early Australian cave paintings that have a distinct vibe like "yo, watch out for this one, guys."

Advertisement

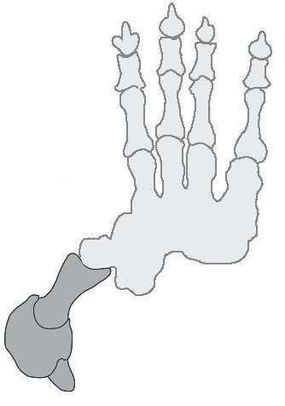

From fossils of Thylacoleo, we know that it was about the size of a modern female lion, and had the lion's huge, crushing jaws. However, the similarities with modern cats ends there, as Thylacoleo's teeth were blunt, and its forelimbs were much stronger than anything you'd see on a feline, suggesting it probably wasn't very fast. But one thing this ancient predator did have was a long, deadly-looking retractable "dew claw" on each semi-opposable thumb.

A new paper in the journal Paleobiology suggests the unusual anatomy of the marsupial carnivore provides clues into a weird predatory behavior we can no longer observe. While modern cats hold caught prey in place with their claws and they kill it with razor-sharp teeth and powerful jaws, Thylacoleo probably did the opposite, using its jaws to hold an animal still while dispatching it by using its giant claws to slash or disembowel its prey. You didn't see that one coming, did you?

According to co-author Dr. Christine Janis, the key to decoding Thylacoleo's predatory behavior lies in its elbow joint. Animals built for running (like dogs) have an elbow joint that allows for backward and forward motion, while monkeys and other climbing animals forfeit the super efficient back-and-forth for more rotational mobility. Modern cats use their forelimbs to grab their prey, so they require some rotation, but also need to be good runners, so their elbow joints have a sort of hybrid shape.

"If Thylacoleo had hunted like a lion using its forelimbs to manipulate its prey, then its elbow joint should have been lion-like," says Janis in a press release. "But, surprisingly, it had a unique elbow joint among living predatory mammals — one that suggested a great deal of rotational capacity of the hand, like an arboreal mammal, but also features not seen in living climbers, that would have stabilized the limb on the ground (suggesting that it was not simply a climber)."

The unusual elbow joint, Janis concluded, was probably used for an activity we don't see in any animal living today: claw-to-death-with-thumb-daggers as primary means of predation.

Advertisement